Project Report

Study Abroad Impact Technical Report

December 2013

Prepared for

Gary Rhodes, Ph.D., Director

Center for Global Education at UCLA

Rosalind Latiner Raby, Ph.D. Director, California Colleges for International Education

By

The Research and Planning Group for California Community Colleges

Terrence Willett, Senior Researcher

Nathan Pellegrin, Senior Researcher

Darla Cooper, Director of Research and Evaluation

December 21, 2013 | Click here to download ![]() PDF version of the report

PDF version of the report

Executive Summary

- A set of 476,708 first-time California community college students was studied to determine differences in key outcomes between study abroad and non-study abroad students.

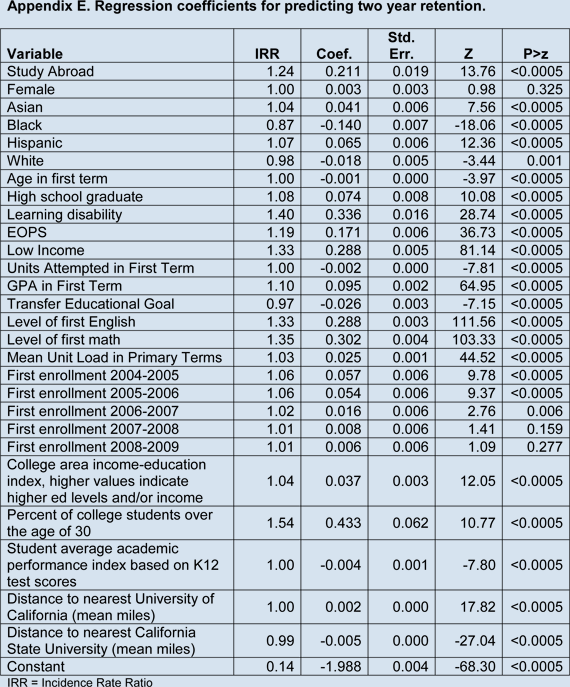

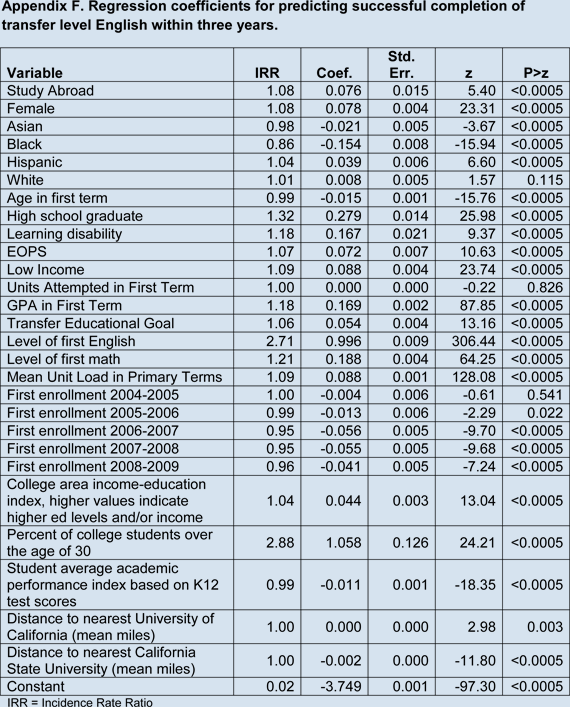

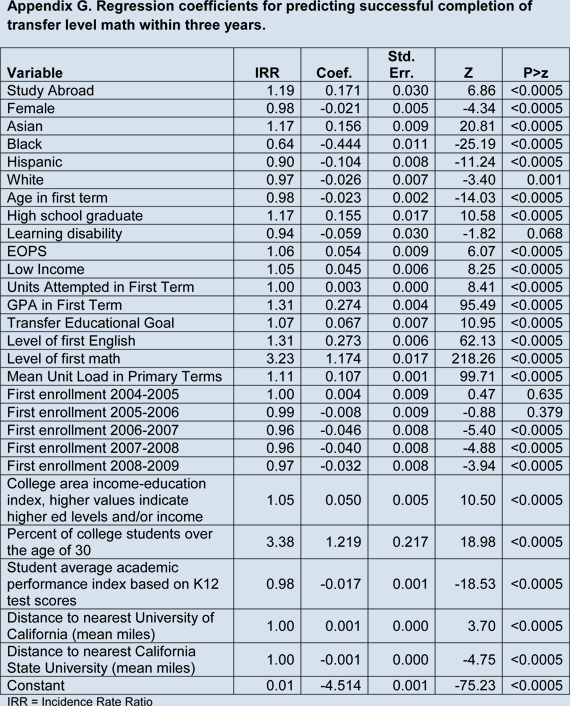

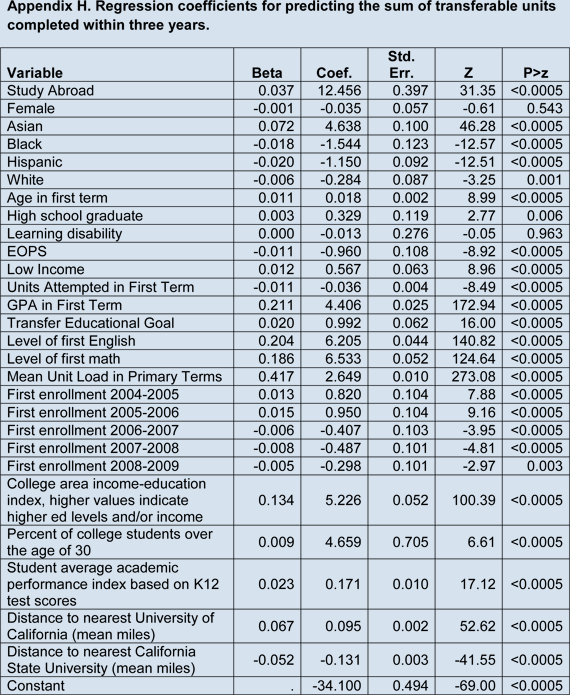

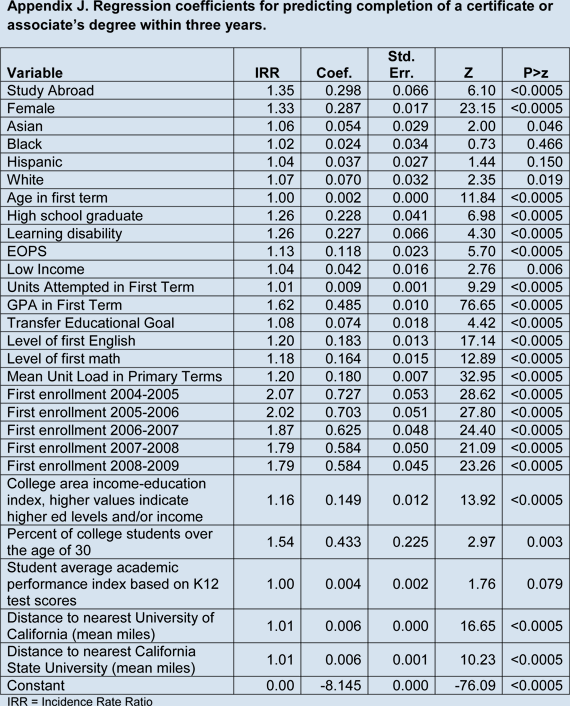

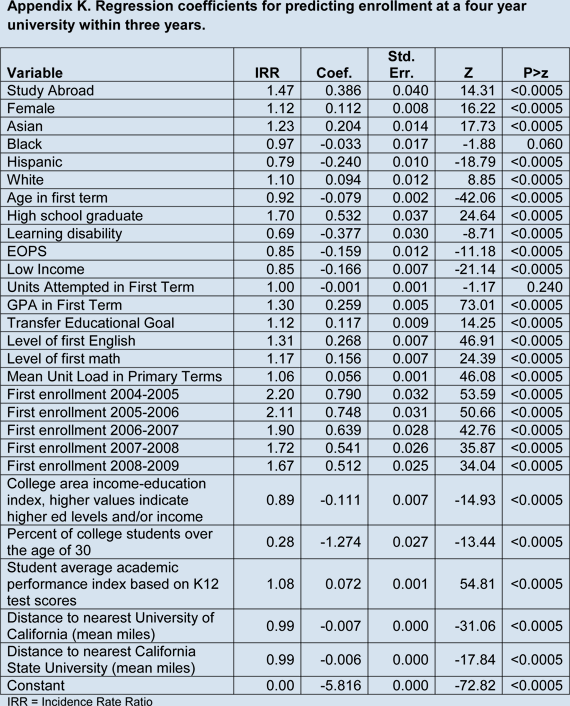

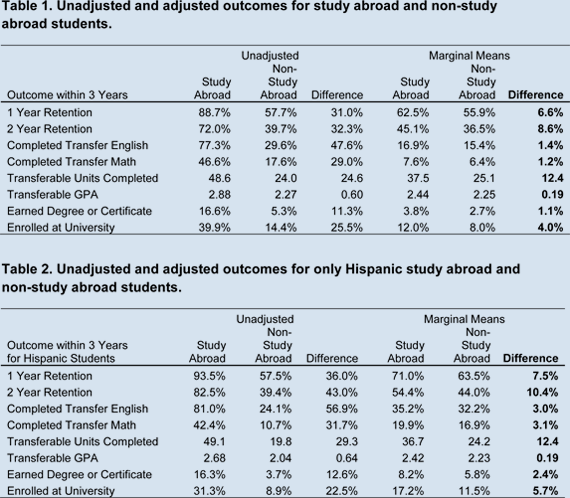

- Poisson and linear regressions were used to control for differences in background variables between study abroad and non-study abroad students.

- Regression-adjusted outcomes (as well as non-adjusted) between study abroad and non-study abroad students showed study abroad students had higher outcomes on:

- One-year retention

- Two-year retention

- Transfer English completion

- Transfer math completion

- Mean transferable units completed

- Transferable GPA

- Degree and certificate completion

- Transfer rates

- The pattern of study abroad students having higher outcomes also held for Hispanic students.

Introduction

Study abroad courses are offered at many colleges to provide students the opportunity to engage with other countries and cultures. A study abroad course is defined in this research as any course that meets primarily outside of the United States of America. At California community colleges, such courses can range in length from a few weeks to an entire semester and be offered in summer or winter intersessions or primary terms. In addition, these courses may be offered as a combination of two or more courses taken concurrently. The goal of study abroad is not only to teach subject-matter, but to use specific curricula that optimize out-of-class experiences to connect students, faculty, and local communities to people, cultures, and contexts beyond local borders (Raby, 2008). Since the mid-1990s, each year about 3,500 California community college students participate in a California Colleges for International Education (CCIE) study abroad program. While study abroad courses are intended to enrich and broaden students from an international perspective, previous studies suggest there may be a positive effect on student outcomes (Indiana University, 2009; Sutton & Rubin, 2010; St. Mary’s College, 2011; see also http://globaledresearch.com/study-abroad-impact.asp). This research described in this report compared academic outcomes of study abroad to non-study abroad students using regression analyses to attempt to control for differences in students’ background variables. The intent was to examine if there was any evidence of study abroad programs being associated with increased academic achievement. In addition, Hispanic students were analyzed to see if any detected associations also held for this group, which is a large proportion of students in California and have historically shown achievement gaps when compared with White and Asian students.

Methods

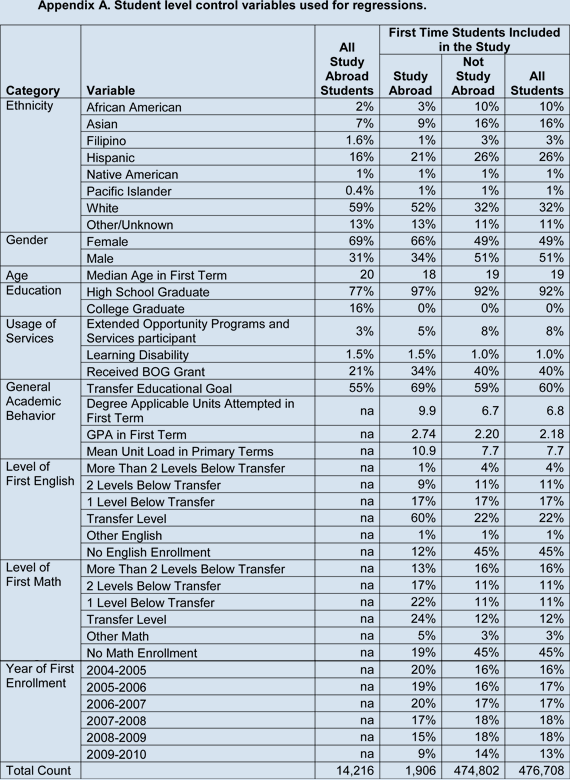

The initial pool of 14,216 study abroad students was from 2,742 study abroad sections at 16 California community college districts representing 29 colleges from 2001 through 2012. Note that at California community colleges, an instance of a course can consist of more than one section number for administrative purposes. For example, a course may have a lab component that divides students into separate labs within the same course 3 offering. About one third of study abroad duplicated enrollments were in a foreign language course with Spanish comprising about half of those duplicated enrollments. A set of descriptors of these study abroad students in Appendix A in the “All Study Abroad Students” column. This includes re-entry students who were more likely to be older and already have a college education as compared to other students.

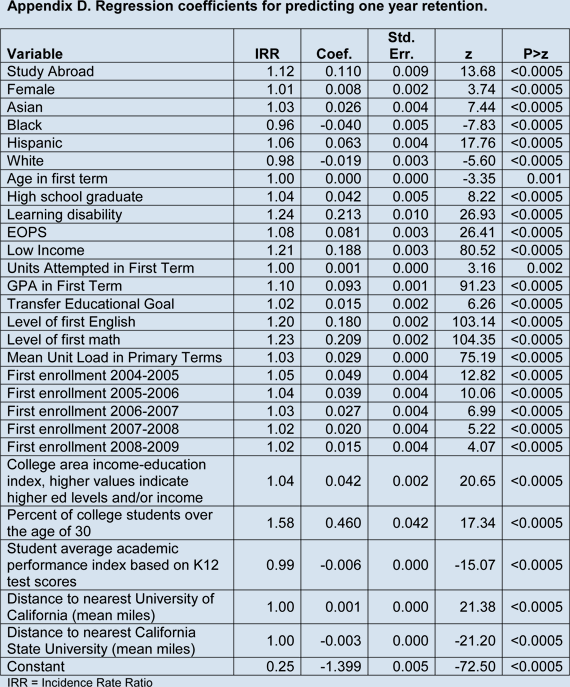

As study abroad students self-selected to take these courses, it was not appropriate to simply compare study abroad participants to all other students. In order to isolate the possible effects of a study abroad program from confounding background variables, it would be best to randomly assign students to participate in study abroad or not. In that way, differences in background variables would be ignorable as they would be more or less evenly distributed between participants and non-participants. As random assignment was not possible, the current study attempted to control for differences between participants and non-participants using post-hoc regression techniques. Regressions statistically control for differences between study abroad and non-study abroad students using a set of background variables such as previous academic performance. Poisson regressions with robust variance were used for all outcomes except for the number of transferable units and transferable grade point average (GPA) where multiple linear regressions were used. Recent research has suggested that Poisson regressions using robust variance have advantages over logistic regressions when predicting binary outcomes (Barros and Hirakata, 2003). These advantages include more accurate error estimations, more interpretable coefficients, and less reliance on difficult to meet assumptions of logistic regression. All independent variables were entered as a single block. STATA 12.1 MP performed the regression analyses.

A set of 476,708 first-time college students who first enrolled between fall 2004 and fall 2009 were selected from the participating college districts and tracked for three years from their initial term of enrollment. This restricted time was selected to balance having more recent data with allowing students enough time to exhibit academic behaviors of interest. The study used data from the California Community College Chancellor’s Office Management Information System (COMIS) to identify study abroad participants and a comparison group of non-study abroad students and to derive outcome and 4 control variables. Data were extracted using SQL Server 2102 Management Studio. This research included first-time college students at participating California community colleges who showed a credit enrollment that was not concurrent with high school enrollment. Of all first-time students at participating districts starting from fall 2004 through fall 2009 based on the selection criteria, there were 1,906 study abroad participants and 474,802 students who did not participate in study abroad during this same time. Study abroad students in this research did not necessarily take study abroad courses in their first term, but could have taken a study abroad course at any time during the three-year tracking period. While focusing on first time students means that findings cannot be generalized to returning students, it does address the group of students typically of most interest to student success personnel and policy makers.

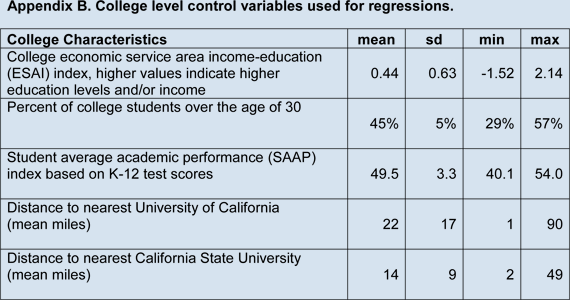

In an effort to account for as many potentially confounding variables as possible, an extensive list of student background variables was gathered from the COMIS database. The data set had minimal missing data issues although students who did not take an English or math course in the time frame of the study had an unknown level of preparation in these areas. Also included in the analysis was a set of college-level factors identified through research conducted by the California Community College Chancellor’s Office Research Unit as being at least moderately statistically associated with academic achievement and attainment. The control variables included:

- Student-Level Factors

- Ethnicity

- Gender

- Age at first term of college enrollments

- Flag for high school graduate

- Flag for learning disability

- Flag for Extended Opportunities Programs and Services (EOPS)

- Flag for received Board of Governor’s fee waiver (low income)

- Degree applicable units attempted in first term

- GPA in first term

- Flag for having identified transfer/award related goal in first term

- Level of first college English course taken ( 0 = no English, 1 = remedial English, 2 = transfer English)

- Level of first college math level ( 0 = no math, 1 = remedial math, 2 = transfer math)

- Mean unit load in primary terms

- Year of enrollment (cohort effect)

- College-Level Factors

- College economic service area index (ESAI), higher values indicate higher levels of educational attainment and/or income (van Ommeren, Liddicoat, and Hom, 2008)

- Percent of students at college over the age of 30 (Accountability and Reporting for California Community Colleges (ARCC) 2007 report based on 2005 data)

- Student average academic performance (SAAP) index based on K-12 test scores (Bahr, Hom & Perry, 2004)

- Distance to nearest University of California

- Distance to nearest California State University

However, it should be kept in mind that other key differences between study abroad and non-study abroad students may not have been fully accounted for due to lack of data availability. Appendices A and B show the values of these indicators in the original data set. It should be noted that some students attend more than one college, referred to as ‘swirl,’ although most students in this study attended only one college.

The outcomes selected for comparison between study abroad and non-study abroad students included:

- One-year retention– Students enrolling in the academic year after their first term of enrollment. For example, a first-time student in fall 2004 would be counted as retained if s/he enrolled in any term during the 2005-2006 academic year.

- Two-year retention– Students enrolling in the second academic year after their first term of enrollment. For example, a first-time student in fall 2004 would be counted as retained in the second year after enrollment if s/he enrolled in any term during the 2006-2007 academic year.

- Transfer English success within 3 years– Students completing a transfer-level English course as defined by taxonomy of program (TOP) codes with a grade of C or better within three years of college entrance.

- Transfer math success within 3 years– Students completing a transfer-level math course as defined by taxonomy of program (TOP) codes with a grade of C or better within three years of college entrance.

- Number of transferable units completed within 3 years– The sum of units coded as transferable successfully completed with a grade of C or better within three years of college entrance.

- Transferable Grade Point Average (GPA) within 3 years– Student’s GPA based on only transferable coursework taken within three years of college entrance.

- Earned degree or certificate within 3 years– Students earning an associate’s degree or certificate of completion by the end of the third year of enrollment, also referred to as earning an award. For example, a first-time student in fall 2004 who earned a degree or certificate by the end of spring 2007 would be flagged as achieving an award.

- Transferred to a four-year institution within 3 years– Students with a record of enrollment at a university after their community college enrollment. Note this indicator does not account for the number or type of courses taken at the university.

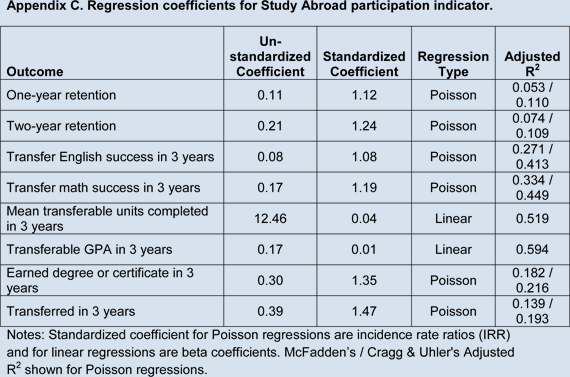

These outcomes are inclusive of outcomes achieved at all participating districts and are not limited to the first college attended. However, students may take classes or earn degrees or certificates at other community colleges not in this study. For the regressions, outcome differences were evaluated using marginal means in addition to unstandardized and standardized coefficients (Appendix C). Marginal means are created from inputting average values for each input variable other than the study abroad participation indicator and examining the difference in outputs for study abroad and non-study abroad students. Marginal means are used to examine relative effect of a treatment variable such as participation in study abroad. The value of each marginal mean should not be interpreted directly (e.g., they are not transfer or graduation rates).

Results

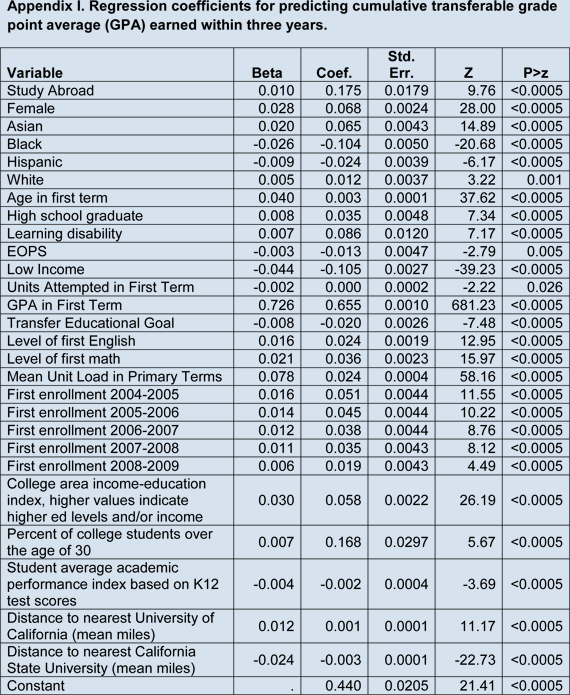

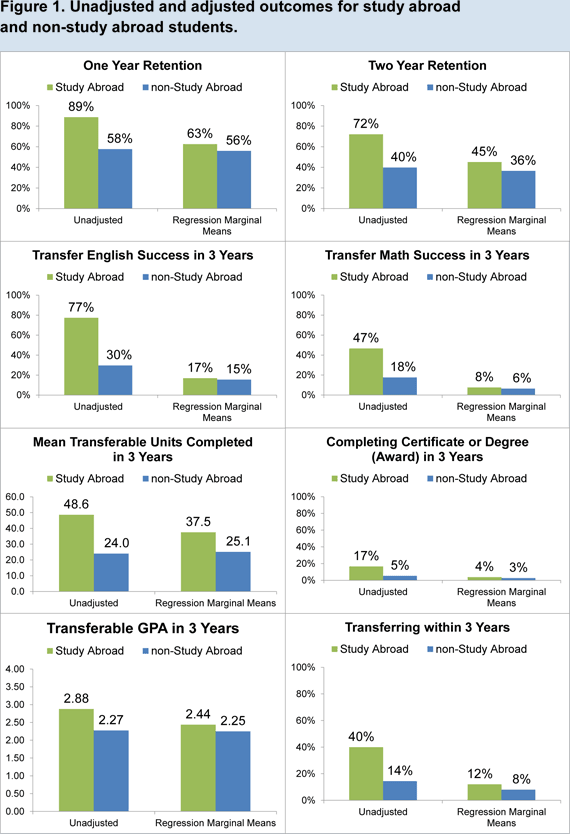

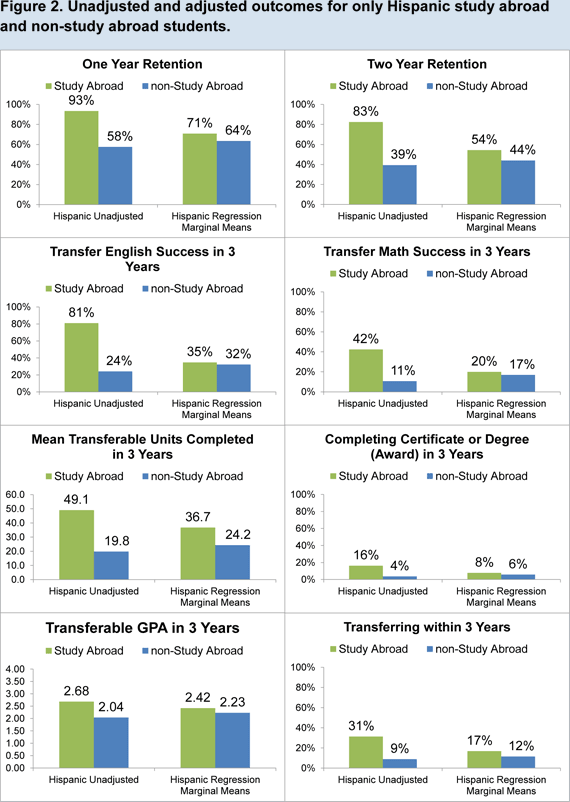

Table 1 shows the outcomes for all the first-time students (1) without statistical adjustment and (2) with adjustment using regression (see Appendices C through K for regression coefficients). Table 2 shows the outcomes for only Hispanic students. In both the unadjusted and adjusted outcomes, study abroad students were higher than non-study abroad students on all outcomes. The differences were generally larger when examining only Hispanic students. Figures 1 and 2 show the outcomes displayed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The effect of the adjustments was to reduce the differences between study abroad and non-study abroad students. Note that all differences were statistically significant; however, given the large sample size, the statistical significance is not as important as the actual practical magnitude of the differences. In other words, it is more important to consider the magnitude of the observed differences, after adjustment, and determine if the effect is of practical significance.

Discussion

In this research, study abroad participation was associated with higher outcomes across a broad array of early, midstream, and terminal outcomes. However, it should be kept in mind that other key differences between study abroad and non-study abroad students may not have been fully accounted for due to lack of data availability. These other variables may include factors such as parents’ education level, personal support networks, individual motivation, employment load, responsibility for dependents, and health conditions.

In finding higher outcomes for study abroad students, it is reasonable to review the mechanisms by which the study abroad program may be directly influencing student achievement. The classic works by Astin (1984) and Tinto (1993) and subsequent research (such as Booth, et al. 2013) illustrate the importance and efficacy of student engagement and students feeling valued in student retention and success. While study abroad courses are not specifically designed to enhance student engagement and success, it may be that the study abroad structure contains several success-enhancing components such as:

- Creating a cohort of limited size that has a shared common experience;

- Incentivizing nurturing behavior from instructors who must ensure student safety;

- Increasing student interaction as they must remain in a group and engage in collaborative activities.

- Interacting with people from a diversity of backgrounds as students apply what they learn in new settings.

- Living in housing situations that reinforce study abroad program academic and social interaction goals.

If these structural factors are in fact contributing to enhanced engagement and success, these could be intentionally promoted within study abroad courses and potentially enhance the effect of such courses. There are also other non-study abroad courses with similar characteristics such as field classes often taught in biology and geology departments. Future research might include these and other types of classes with similar structures to further explore the possible effects of off-campus cohort experiences. In addition, the greater effect size seen for Hispanic students suggests that study abroad and similar courses could be considered as part of a mix of strategies to address achievement gaps.

References

Astin, A.W. (1984). Student Involvement: A Developmental Theory for Higher. Education. Journal of College Student Personnel, 25, 297-308.

Barros, A. and Hirakata, V. (2003). Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 3:21.

Bahr, P., Hom, W., and Perry, P. (2004). Student Readiness for Postsecondary Coursework: Developing a College-Level Measure of Student Average Academic Preparation. The Journal of Applied Research in the Community College, 12:1, 7-16.

Booth, K.; Cooper, D.; Karandjeff, K.; Large, M.; Pellegrin, N.; Purnell, R.; Rodriquez-Kiino, D.; Schiorring, E.; and Willett, T. (2013). Using student voices to redefine support: What community college students say institutions, instructors and others can do to help them succeed. The Research and Planning Group for California Community Colleges, Berkeley, CA. Retrieved 4/26/2013 from http://rpgroup.org/sites/default/files/StudentPerspectivesResearchReportJan2013.pdf

Indiana University. (2009). Overseas study at Indiana University Bloomington: Plans, participation, and outcomes. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Retrieved 4/26/2013 from http://www.iu.edu/~uirr/reports/special/doc/Overseas Study - Executive Summary.pdf

Raby, Rosalind Latiner. (2008). Meeting America’s global education challenge: Expanding education abroad at U.S. community colleges. Institute of International Education Study Abroad White Paper Series 3 (September 2008). New York: Institute for International Education Press.

St. Mary’s College Office of Institutional Research (July 2011). St. Mary’s Comparison of 2008, 2009, and 2010 Graduates: St. Mary’s GPA Outcomes for Study Abroad Students, Notre Dame, Indiana. Retrieved 4/26/2013 from https://cwil.saintmarys.edu/files/cwil/images/bbreviated_report_as_revised_on_12-07-09_doc.pdf

Sutton, R. C., & Rubin, D. L. (2010, Jun.). Documenting the academic impact of study abroad: Final report of the GLOSSARI project. Retrieved 4/26/2013 from http://glossari.uga.edu/datasets/pdfs/FINAL.pdf

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition (2nd Ed.), The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

van Ommerman, A., Liddicoat, C., Hom, W. (2008). Developing Service Area Indices for Community Colleges: California's Method and Experience. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 32:7, 463 — 479.